Teaching in a new country allows you to immerse yourself in the culture and language fully. For AP English teacher Tim Willcutts at BASIS International School Shenzhen, deciding to learn Mandarin was the first step to getting the most out of his time teaching in China. Tim shares firsthand his journey in learning Mandarin, full of successes and a few challenges.

When I arrived in China in 2019 to teach English at BASIS International School Shenzhen, my first order of business–before the teaching began–was to find a Chinese teacher. Of all the benefits of living abroad, none seemed clearer to me than the opportunity to converse with local people in their language, transforming my own frame of reference in the process.

A colleague put me in touch with Lily, one of many freelance teachers who advertise their services on the WeChat app and will meet students in any Shenzhen neighborhood for one-on-one instruction. At a Pizza Hut near my apartment, Lily introduced me to the four tones of Mandarin Chinese–mā (level and high), má (rising), mǎ (falling, then rising), and mà (quickly falling)–by training me to count from one to ten. Getting these four tones wrong, I soon discovered, virtually guaranteed no Chinese person would understand what I was trying to say to them. What’s more, many Chinese words sound identical to each other–apart from their tones–so understanding what other people were saying would require me to develop an extraordinarily sensitive ear for the music and texture of speech. I suddenly felt as though I had decided to start learning classical violin at the age of 41.

Over the next few months, I enjoyed small victories–the first time I understood the word kuài dì (express delivery) on a phone call with a courier, my developing ability to shout out the correct number in a game of sé zĭ (dice) at the local pub–but I also realized that learning Mandarin would take much more time than I’d needed to learn Spanish, the first non-English language I’d studied. Lily taught me that Mandarin does not have verb tenses, not in the way English and Spanish do. I would have to remember to attach various suffixes to the ends of my verbs, along with other connecting words, to clarify whether I was talking about the present or the future or the past–or the very recent past. Determined to reach some critical threshold where all the frustration I was experiencing would give way to spontaneous expression, I worked my way through various online Chinese learning apps, played Chinese conversation videos on YouTube while I slept, and embarrassed myself before countless taxi drivers generous enough to try to piece together what I was saying.

The biggest mistake I made as a beginning student of Mandarin was thinking I could get away without learning hànzì, the written Chinese characters. Impatient to develop my conversational skills, I had insisted on only learning pīnyīn, the Romanization system to translate all Mandarin sounds into the Latin alphabet.

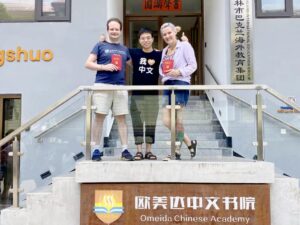

This all changed in 2021, when I started taking classes at Omeida Academy in the small mountain town of Yangshuo in Guangxi Province, about a three-hour train ride from Shenzhen. The teachers and advanced students at Omeida instilled in me an appreciation for the beauty and versatility of Chinese characters. Intimidating in their visual intricacy and sheer number, the characters also unlock the logic of the Chinese language. Like scouring through the world’s largest jigsaw puzzle, one starts to enjoy playing with the pieces, seeing how they fit together. Take the character for “electric,” 电 (diàn), for example, and hook it up with the character for “shadow,” 影 (yĭng), and you have 电影 (diànyĭng), “electric shadow,” which means movie. I spent my next five vacations from BASIS at Omeida, initiating myself into a rich subculture of expatriates cheering each other on, sharing strategies and books and apps in a collective effort to edge a little closer to seeing and speaking and hearing the world in Chinese.

I have now reached a point where using Mandarin is genuinely fun, because the shop clerks and taxi drivers and strangers in the park understand enough of what I’m saying to engage in a friendly banter; and I understand them well enough to feel a bit more connected to the community in which I live. Still very much a beginner, I now at least have a foothold in the language and can expect to steadily improve so long as I maintain my discipline. In fact, on a recent trip to the dentist, the doctor was so impressed with a phrase I spoke in Chinese he told his assistants to stop translating his instructions into English. I had to listen very closely to know when I should 咬 (“bite”) and when I should 开口 (“open mouth”). All part of the joy and challenge of learning Mandarin!

Of all the benefits of living abroad, none seemed clearer to me than the opportunity to converse with local people in their language, transforming my own frame of reference in the process.

Tim Willcutts is an AP English teacher at BASIS International School Shenzhen. This is his fourth year teaching at BISZ.

For more information on teaching with BASIS International Schools, visit our careers website.