The Story We Are Creating

In our AP World History classroom, we believe that history is not a static collection of dates and people, but a dynamic, living story of which we are still a part. We are creating a learning environment where students are not passive recipients of information but active historical detectives, connecting global patterns to their personal lives. Our recent project, “The Columbian Exchange on Our Plates,” exemplifies this method, transforming abstract historical trade routes into a tangible and delicious investigation into the very heart of Chinese cuisine.

Course: AP World History: Modern

Unit: Unit 4: Transoceanic Interconnections (c. 1450 – c. 1750)

Central Question: How did the Columbian Exchange fundamentally reshape global economies, cultures, and diets?

The Spark: Engaging Personal Interest

The activity began not with a textbook, but with a simple, relatable question:

“What is your favorite Chinese dish?”

The whiteboard quickly filled with a vibrant and mouth-watering list:

- Kung Pao Chicken

- Mapo Tofu

- Sweet and Sour Pork

- Hot Pot

- Scrambled Eggs with Tomatoes

The energy in the room was immediate and personal. Students were already invested.

Then came the pivotal, inquiry-based question: “Looking at this list, how many of these iconic dishes could have existed in China before the year 1492?“

A thoughtful silence fell, followed by hesitant guesses. “The pork, for sure,” one student offered. “And the tofu,” added another. This was the perfect entry point into the core content of the Columbian Exchange. We introduced the concept, defining it as the widespread transfer of plants, animals, culture, human populations, technology, and ideas between the Americas and the Old World in the 15th and 16th centuries.

The Active Learning Task: Culinary Detective Work

Students were tasked with choosing one dish from the board and becoming its “historian.” Their mission was to deconstruct it, identifying key ingredients and tracing their origins. They were provided with a curated list of resources, including the Pulitzer Center’s “Food Origins Map,” academic databases, and their textbook.

The classroom transformed into a hub of active research. The noise was the sound of engagement: the frantic clicking of their keyboards and the buzz of collaborative conversation.

A student researching Kung Pao Chicken had a breakthrough: “The chili peppers and the peanuts! Both are from the Americas. This dish wouldn’t be spicy and wouldn’t have peanuts without the Columbian Exchange!”

Another investigating Scrambled Eggs with Tomatoes realized, “This is the most direct example! Tomatoes are from the the New World. This simple, home-cooked dish is a product of global interconnection.”

A group deconstructing Sweet and Sour Pork noted, “The sauce is built on sugar and tomatoes. Large-scale sugar production in the Americas and the tomato both arrived after 1492. The ‘sweet and sour’ flavor profile as we know it was transformed.”

A student looking at Mapo Tofu discovered, “While the tofu and Sichuan peppercorns are ancient, the chili oil that gives it its characteristic red color and fiery taste is made from a New World plant. Before the 16th century, this dish would have been fundamentally different.”

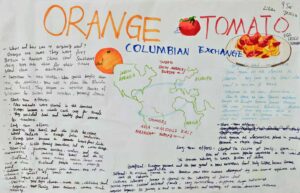

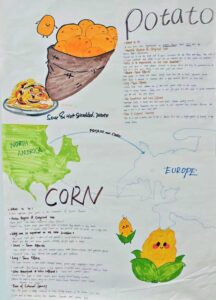

Synthesizing and Storytelling: The Annotated Map

To visualize their learning, students created digital or physical “Culinary Journey Maps.” They plotted the transoceanic voyage of their ingredients from the Americas (“New World”) to various ports and regions in China. These maps were more than just lines; they were annotated stories. Students had to explain:

The Origin: Where in the Americas the ingredient originated (e.g., chili peppers from Bolivia, peanuts from Brazil, tomatoes from the Andes, sweet potatoes from Central America).

The Journey: The likely route (e.g., via Spanish Galleons from Acapulco to Manila, and then into coastal Chinese ports like Fujian and Guangzhou through maritime trade networks).

The Impact: How the adoption of this new ingredient altered Chinese cuisine, agriculture, and society (e.g., how the sweet potato became a crucial famine food, contributing to population growth, or how chili peppers revolutionized regional cuisines, leading to the fiery profiles of Sichuan and Hunan cooking).

Highlighting Student Engagement & Critical Thinking:

This activity was a masterclass in the skills central to AP success and historical thinking.

Causation & Continuity/Change: Students didn’t just memorize that the Columbian Exchange happened; they saw its ongoing effects on a cuisine they knew and loved. They understood the causation between the Manila Galleon Trade and the spice level of their favorite dish.

Sourcing & Argumentation: They evaluated digital sources to determine credible information about food history, building their research skills.

Making Connections: The most powerful moment was the synthesis, when a student drew a line on their map from the Andes to Sichuan and realized they were looking at the origin story of the chili pepper in their Mapo Tofu. History was no longer distant; it was on their spoon.

Conclusion: The Story Continues

The “Columbian Exchange on Our Plates” project did more than teach a key element of the AP curriculum. It empowered students to see familiar cuisine as a living record of global history. They left the activity with an understanding that the flavors of modern China are a direct result of the transoceanic connections forged in the early modern period.

By starting with their favorite Chinese dishes, we made Unit 4’s complex web of connections personal, memorable, and deeply engaging. This is the story we are creating every day: one where students are active, curious, and empowered learners, ready to tackle the AP exam and, more importantly, to understand the world and their place in it, one dish at a time.

Tim Torres

AP World History Instructor

Business Innovation & Entrepreneurship Instructor

BASIS International & Bilingual Schools Wuhan

For more information on teaching with BASIS International Schools, visit our careers website.

Watch the recording of our live webinar about teaching at BASIS International & Bilingual Schools Wuhan on our YouTube channel.

Explore more stories of teaching AP classes at BASIS International & Bilingual Schools here.